WI-HER Series: Breaking Barriers and Raising the Bar on Measurement – Part III: Measuring Corporate Women’s Leadership and Economic Empowerment Programs

By Tisa Barrios Wilson, Program Associate

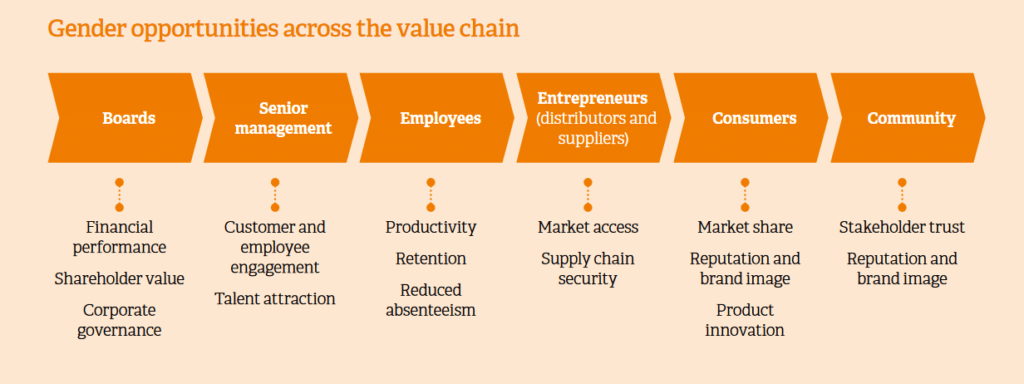

Despite research that shows girls perform better educationally across the world,1 the translation of that performance to success and equality in the workforce remains a challenge. Known as the Global Gender Pay Gap,2 women’s earnings remain, on average, between 10 and 30% less than men’s globally. These figures understate the extent of gender pay gaps in developing countries where informal self-employment is more common.3,4 Globally, women face a multitude of challenges when entering the workforce including the disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care and domestic work, less access to social protection, higher risk for violence and harassment, less access to financial institutions, and legal restrictions including laws preventing women from working in specific jobs, lack of laws on sexual harassment in the workplace, and laws where husbands can legally prevent their wives from working, among others. 4 It doesn’t look much better for women’s leadership in the workplace. As of 2018, women hold only 24% of senior roles globally, and among the world’s largest 500 companies only 10.9% of senior executives of women.5 However, companies are beginning to recognize the benefits of investing in women at all stages of their ‘value chain’ which is the set of activities that a company executes in order to deliver a product or service for the market, from the board room to the community in which they operate (see figure below). To yield a ‘high return on investment’ (ROI), more businesses are advancing women’s leadership initiatives within their companies and economic empowerment programming for women in their value chain. However, these programs vary in rigor in how they measure both the benefits to the company and the benefits to the women themselves. Without rigorous measurement, how do we know what works and what doesn’t?

Source: CDC Group plc, What we’ve learnt about women’s economic empowerment, 2018.

This blog is the third in series about WI-HER’s approach to measurement (see Part I and Part II). In our first blog we talked about measuring women’s empowerment – which includes “a woman’s ability to participate equally in existing markets; their access to and control over productive resources, access to decent work, control over their own time, lives and bodies; and increased voice, agency and meaningful participation in economic decision-making at all levels from the household to international institutions.”4 This blog expands on this concept and will explore the current evidence on corporate women’s leadership and empowerment programs, identify the gaps in measurement, and provide recommendations to address these gaps.

The business-case for investing in women

The case for economically empowering women is multifaceted. There is a moral argument that women’s economic empowerment is central to realizing gender equality and advancing human rights, there is a macroeconomic argument that when women work economies grow, and that closing gender gaps in the workplace are key to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs).4 But here, let’s focus on evidence for why businesses should invest in women’s empowerment at all levels across the value chain, from board members, to entrepreneurs, to consumers, and within the communities they target. Here are some highlights:

- Women are good for company profits. A urvey from Peterson Institute for International Economics of 21,980 firms from 91 countries and found that having women at the executive level significantly increases net margins.6 A similar 2018 study from McKinsey, drawing on data from more than 1,000 companies covering 12 countries, found that gender diversity in the executive team not only increased profitability by more than 21% (in terms of earnings before interest and taxes, or EBIT) but also contributed to longer-term value creation (or economic profit) by 27%.7

- Women make companies and supply chains more productive. Investing in women’s skills and facilitating access to resources has been linked to improved product quality and increased efficiency output in a number of instances. Human Resources (HR) policies that address gender-specific needs (such as maternal and paternal paid leave) can improve recruitment and retention and reduce absenteeism. Addressing issues of gender-based violence (whether occurring at home or in the workplace) can also help reduce absenteeism, presenteeism (loss of productivity resulting from health problems and/or personal issues), and turnover.8 Furthermore, having female senior leaders creates less gender discrimination in recruitment, promotion, and retention giving a company a better chance of hiring and keeping the most qualified people.7

- Women make businesses more innovative. An analysis of Fortune 500 companies found that companies that have women in senior executive roles experience ‘innovation intensity’ and produce more patents by an average of 20% more than teams with male leaders.7

- Gender diversity inspires respect. According to the GFP Index, Fortune’s “most admired” companies have twice as many women at the senior management level than less reputable companies.5

- Women are consumers. Women control 64% of household spending, which is $29 trillion of consumer spending worldwide. They are a key consumer market that companies need to understand and cater to if they want to achieve market growth.8

Where are the gaps?

Several companies have invested in broader Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs aimed at empowering women in their own value chain and in their broader consumer/ client communities. Some examples include GAP’s P.A.C.E. program that provides skills training to female garment workers in southeast Asia;9 the World Cocoa Foundation’s CocoaAction which builds women’s leadership within cocoa farming in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire;10 and Coca Cola’s CSR 5by20 which provides training, financial services and mentoring for women entrepreneurs at the community level.11

A 2014 report by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), Dalberg, and Witter Ventures found that only three of the 31 corporate-funded women’s economic empowerment programs included in the analysis completed a full, rigorous impact evaluation.12 Without evaluation strategies and processes built into program design with rigorous measurement and data collection, companies cannot assess the social and economic impact for the women who participate, their families and communities, and the ROI for the businesses themselves. There has been increasing concern in the international development community that some of these globally reaching CSR programs are not designed to make long-term, meaningful headway on women’s empowerment, but rather satisfied with surface-level and short-term fixes.12-14 Instituting a comprehensive measurement and evaluation plan is an essential first step to understanding economic empowerment program’s impact and to give meaningful impact to the significant investments that many of these companies are contributing.

A comprehensive approach

WI-HER recommends a comprehensive framework when measuring women’s leadership and economic empowerment programs that measures social and economic impact for the women participating in the program, and for the business’ bottom line, growth, efficiency and diversity, that considers short- term monitoring and longer-term impact. Linking both business impact and social impact to these investments, and rigorously measuring both, makes it more likely that businesses will continue successful programs, scale them, and share them publicly for replication.14 These measurements and the assessment and reporting should be integrated into the design of the program at its inception and not as an afterthought.

Here are some factors that WI-HER recommends be considered when developing an evaluation framework that will vary by the type of empowerment program implemented:15

Measuring impact on women:

- Women report that they experience respect, influence and voice within the company and the sector

- Women report that they experience increased respect, influence, and voice in their family, and in the community

- Profits and revenues (for an entrepreneurial program) or regularity of employment, hours works, and income earned

- Household income, expenditure, savings and control over it

- Women’s well-being, including indicators of happiness, self-esteem, satisfaction with work and life, and stress levels

- Choice and decision-making in the company or in family and public life

- ‘Multiplier effects’ or benefits on their families and communities

Measure ROI for businesses:

- Gender parity in the executive team and other levels within the company

- Employee retention, satisfaction, absenteeism, and presenteeism

- Company productivity – production quality, output, and yield

- Increased innovation (number of new patents, new product sales, etc. depending on the sector)

- Increased Profit that can be attributed to investment in the women’s leadership/economic empowerment programs

- Company reputation

There is a tremendous opportunity for private companies to change women’s lives and create a sustained impact in the communities in which they work while also improving their own business practices and bottom line profits. These benefits are not mutually exclusive. While incredible work is being done, it is critical to be measuring and evaluating these programs at every step of the way to ensure that these programs are actually helping improve the lives of women. Finding ways to measure ‘empowerment’13 is crucial to holding programs accountable and for understanding what works and what does not.

For more information on WI-HER’s approach measurement, please contact our measurement, evaluation, and learning team at evaluationandlearning@wi-her.org.

References:

- The weaker sex. The Economist. 2015.

- The global gender gap report 2018. Cologny/Geneva: 2018. http://www.fachportal-paedagogik.de/fis_bildung/suche/fis_set.html?FId=A29823.

- World Bank. Gender at work: A companion to the world development report on jobs. . 2014.

- UN Women. Facts and figures: Economic empowerment. http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures. Updated 2018.

- Weber Shandick. Gender forward pioneer index: World’s most reputable companies have more women in senior management. 2016.

- Noland M, Moran T, Kotschwar B. Is gender diversity profitable? evidence from a global survey. Peterson Institute for International Economics. 2016.

- Hunt V, Yee L, Prince S, Dixon-Fyle S. Delivering through diversity. McKinsey and Company. 2018.

- Katherine Fritz, Genevieve Smith, & Marissa Wesely. The next sustainability frontier: Gender equity as a business imperative. 2017.

- Nanda, P., Mishra, A., Walia, S., Sharma, S., Weiss, E., Abrahamson, J. Advancing women, changing lives: An evaluation of gap inc.’s P.A.C.E. program. 2013. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/PACE_Report_PRINT_singles_lo.pdf.

- World Cocoa Foundation. CocoaAction monitoring and guide. 2016.

- Jeni Klugman, Jennifer Parsons and Tatiana Melnikova. Working to empower girls in nigeria highlights of the educating nigerian girls in new enterprises (ENGINE) program. Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security. 2018.

- Ibadet Dervishaj Reller. The business case for women’s economic empowerment: An integrated approach. Perspectives: The ICRW Blog Web site. http://scholar.aci.info/view/1495c5203e476db0388/14b13cd9a7e4cb3014d. Updated 2015.

- Thompson L. Who really benefits from corporate-run women’s empowerment programmes? Equal Times. 2019.

- Midgley L, Wesely M. Three ways businesses can improve their women’s economic empowerment programs. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2018.

- Mayra Buvinic and Rebecca Furst-Nichols. MEASURING WOMEN’S ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT: Companion to A roadmap for promoting women’s economic empowerment. United Nations Foundation and ExxonMobil Foundation. 2013.