Meet the Expert: Dr. Francisca Mutapi of TIBA Partnership

Interview conducted by Eileen Liang-Massey, WI-HER Senior Associate

In working with BMGF on their Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) Gender Integration strategy, we had the privilege of meeting, learning from, and collaborating with Dr. Francisca Mutapi, who is the Deputy Director of the TIBA Partnership. TIBA strives to translate its Africa-led research endeavors into health technologies and policies that reduce the burden and threat of NTDs in Africa and build local research capacity for tackling infectious diseases. Learn more about Dr. Mutapi and her important work through this insightful interview about her career, her work in neglected tropical diseases, and her vision for the future.

What are you an expert in? What is your work about?

I have been working on infectious diseases for the past 25 years. I am in a very fortunate position where I straddle two countries: all my fieldwork is based in Zimbabwe, which is where I’m originally from, and my lab work is mostly in the UK. This gives me access to funding programs within Western institutions while also allowing me to work in African countries with diseases I know well. Being from Zimbabwe gives me the insight to connect with people in the rural villages, which is very difficult to do without a connection. That has been a very valuable aspect of my work.

The specific neglected tropical disease (NTD) with which I have spent most of my working life is schistosomiasis, commonly known as bilharzia, and its old name snail fever. In Africa, it is the second (to malaria) most important parasitic disease of public health concern. Globally, about 240 million people are affected by bilharzia, with about 700 million people living in bilharzia endemic areas; 90% of affected people live in Africa.

The people most affected by bilharzia are women and children because of their patterns of exposure to the parasites. They more frequently come into contact with fresh water in rivers and dams than men. This exposes them to infection by bilharzia parasites, which are released into the water from freshwater snails.

My research has focused on finding effective tools and strategies to control this infection in low-resource settings. Our research group has shown that disease or pathology, such as damage to the urogenital tract, develops very quickly after infection. We have discovered that within three months of infection, the damage already begins, but what we have also discovered is that early forms of this disease can be reversed with treatment. So, one of my biggest drives over the last 15 years has been to get us to treat children under the age of five, a group that had been neglected in national bilharzia treatment programs.

I always say that bilharzia is an unnecessary disease because it is preventable and treatable. We have a very cheap drug that is very effective in treating bilharzia. It is safe and works very well—you just take a single dose. So, the fact that, as a world, we have failed to control this disease tells me that we are not prioritizing it.

I am also concerned about it because bilharzia affects the whole life span, from childhood to adulthood. It is an insidious infection that touches every aspect of normal health, growth, and development. In children under five years of age, apart from clinical pathology, the disease is associated with stunting and poor cognitive development. In Shona, my mother tongue, we call bilharzia “chirwere chechipfungwa,” meaning “a disease of the thinking process.” This is because the elders knew that the kids affected by bilharzia don’t do so well at school both physically and academically.

Highlight a pivotal time when you saw the shift that led to where you are now.

When I came to work in bilharzia, everybody focused on teenagers and older people. And when I questioned, “Why are we not looking at younger children, those aged five years and below?” The explanation was largely that these children did not go to the water and were not infected. And I’m sitting there thinking, “C’mon, I have spent time in rural Zimbabwe. I have seen very young children with the classic symptom of bilharzia: peeing blood. Nonetheless, as a scientist, I knew that no number of anecdotes or personal experiences was going to change policy; I needed to go and collect the evidence. So, a few colleagues and I started conducting small studies to quantify infection in children aged five years and below.

At this stage, the World Health Organization (WHO), recognizing the growing need to investigate infections in the younger age group, funded our team and several others to investigate the safety and efficacy of the drug used to treat bilharzia—praziquantel. This was important because younger children were originally excluded from bilharzia treatment because the original clinical trials, conducted in the 1970s, had been conducted in people aged six years and above; essentially, the drug’s safety and efficacy in the younger age group had not been systematically evaluated.

So, we decided to conduct a comprehensive study to generate the evidence to demonstrate that children do go out to the water, they do pick up the infection, and they do develop pathology from these childhood infections. More importantly, the study evaluated the safety and efficacy of the drug in treating bilharzia in these children. Our research group did that in 2010 and the results were fantastic. We saw that, in some villages, over 30% of children under the age of five had the infection, and they were peeing blood because they started having urogenital tract damage from the parasite eggs in their urine—this was the damage that was supposed to be ‘insignificant.’ Then we treated them: the drug was effective, killing the parasites and reversing the disease damage. In addition, we recorded even fewer side effects in this age group than in older children.

After that, the WHO convened a meeting where we and the other groups working on the same problem presented our findings. That meeting concluded that preschool-age children (children five years and below) were being exposed to infection and needed to be treated. The meeting also concluded that praziquantel was safe and effective at treating bilharzia in this age group. As a result, the WHO now recommends that preschool children be treated for bilharzia. I calculated that this means 50 million children aged five and younger are now eligible for bilharzia treatment.

What is your vision for the next 10 years? What do you hope to achieve, or how do you expect the field you work in will evolve?

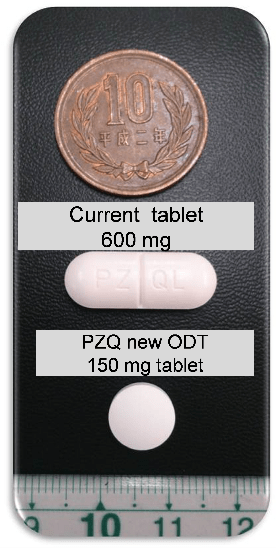

The formulation of praziquantel that we used for our studies in 2010 was a large tablet that is bitter. To give it to the preschool children, we had to break it into smaller pieces to make the correct dose and crush it into powder so the children could swallow it safely. As if that was not bad enough, it is also bitter, making it unpalatable for the little ones, so we had to mix it with squash or a sweet drink. At that same meeting convened by the WHO, we recommended the necessity of a formulation of praziquantel that is child-friendly.

Fast forward 10 years. With a lot of work in the background by my research group and a stellar effort by other colleagues and the Pediatric Praziquantel Consortium, we now have a child-friendly version of the drug. It is small, orally dispersible, and does not have a bitter taste; you put it on the child’s tongue, and it dissolves. The new formulation completed phase three clinical trials in Africa and received a positive evaluation from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) a few months ago. Stakeholders and endemic countries plan to deploy this new formulation to treat preschool children in national programs.

What is my vision for the next ten years? Simple: I want to see the pediatric formulation made available to all 50 million preschool-age children in Africa who need it. This is what I am now working towards.

This is ambitious but an easier journey compared to where we started. It has taken time—over a decade to get to a place where preschool children can be treated for bilharzia and where a suitable formulation for treating them is available—but I have learned from so many examples that we have to invest time, no matter how slowly things may seem to be progressing.

My approach to bilharzia control is that we are building a house, brick by brick. We are clear on the type of house we are building: it is the “successful control and subsequent elimination of schistosomiasis.” I know what this house looks like, but I cannot 3D print the house. It must be built brick by brick. For any disease control or public health measure, you need a lot of tools in your toolbox—these are your building bricks. You cannot rely on just a single control measure—we know this from experience, such as with antibiotic resistance, which is neither sustainable nor resilient.

Since we are never going to have a single silver bullet for eliminating bilharzia, I’m always encouraging research funders to look further, fund long-term, and change the way they evaluate the success of a research or implementation program. Go beyond the publications to see where in the pathway to impact the research fits. Has it taken you a step closer to an ultimate goal? That in itself should be an important aspect of evaluation.

Legacy is critical for sustainability and local agency. I have been conducting research on bilharzia for over 25 years now. What is often overlooked is that I have not conducted this work in a research vacuum. Not only has the research led to policy changes with direct human benefits, it has also done two things: first, several thousands of children have been treated for bilharzia, other worm infections, and malaria directly by our research team as part of our studies; and, second we have trained a critical mass of health workers, clinicians, pharmacists, and research scientists who are now working in the full spectrum of the health system. For example, my colleague in Zimbabwe and I have trained over 150 people over 25 years. The remarkable aspect of this is that over 90% of those we have trained are based in Africa, predominantly in Zimbabwe, and are all still working on NTDs. So if I get run over by a bus tomorrow, the work will continue because my colleague and I have made about one hundred of ourselves.

I have always looked to work with people in endemic areas who are cleverer and more passionate than me—that ensures the research work is relevant and sustainable, and any health gains are maintained. I’m investing in the future, ensuring that people from endemic countries have the best knowledge, the best expertise, and the best equipment to control bilharzia in their home countries. This speaks to WHO’s recommendation of country-ownership and country leadership for NTD control

What motivates you to do the work you do?

I’m an academic. I believe in knowledge made useful. I’ve always felt that the destination for my research should not just be a fantastic Nature paper (although a Nature paper is nice of course), rather it should be to improve the quality of life for the populations I work in. This has been the fight. Because up to 10 years ago, academia did not give the same weight to researchers conducting translational research as to those conducting fundamental laboratory-based research. I’m an immuno-epidemiologist. I want my immunology research to have a destination in the populations that I’m working with, and to have it very quickly. So, I want to be working as closely as I can with the affected populations. I want to be closing circles when delivering an intervention, working on the full innovation to application pathway. I don’t want to come into a population and say, “Look at this brilliant treatment I have come up with from my superb immunology research,” only for the community to say, “Yes, but it doesn’t taste right. It’s not the right color. We don’t want it.”

Over the years, I have learned that you really have to understand not just your innovation but how it fits into the socio-cultural context of where you will deploy it. And then make sure you take the community with you. Because if you do not have customers, you can have the most brilliant product, but it’s not going to fly off the shelf. The customers, the community, have to appreciate and demand it.

This has pushed me to work a lot within communities. I want to showcase the impact that can be achieved when you work with community members, both those affected and those delivering the health care. This is why we recently started our project focusing on people living with NTDs, putting them at the center of research, policy formulation, and NTD control. This goes beyond the tokenistic practice of community engagement that can often be a box-ticking exercise in grant applications. Affected voices have been missing in a lot of public health initiatives. For all our public health interventions, these are our customers and we have to listen to them. This year’s World NTD Day’s rallying call is “Unite. Act. Eliminate.” By ignoring affected voices, we are failing at the first hurdle!

Do you have a message for all of us who work in Neglected Tropical Diseases?

It is time to listen to the Affected Voices. They have been shouting in a vacuum for years and we have not been listening. We will develop better interventions, accelerate progress, and have better chances of eliminating NTDs if we take the time to engage with and listen to Affected Voices.