Masculinity, Ogo Culture, and Access to Healthcare in Ebonyi State, Nigeria

By SJ Renfroe, WI-HER Senior Associate

In some parts of Ebonyi State, Nigeria, men’s lives are shaped by “Ogo culture,” which includes a belief system around masculinity and cultural practices for boys’ initiation into manhood. During the “Ogo Initiation,” boys around the age of eight or nine years old go into local towns to collect food left outside for them by community members. While the boys are collecting food, no one, particularly women and children, can see these boys because the prevailing cultural belief is that they will become barren or deaf. These young boys bring the collected food to younger boys, who are in earlier stages of the initiation and are not allowed to go outside until that stage has concluded.

“During this period, they are not allowed to seek healthcare even if they are exposed to harsh conditions like cold weather. The tradition emphasizes that men must endure and withstand every challenge,” explains Pastor Uka Chima from the Afikpo South Local Government Authority (LGA).

Pastor Chima remembers a time when this initiation practice resulted in the death of a boy who was not permitted to access medical care when he urgently needed it. He also explains that “women in labor may not be able to come out during the ‘Ogo’ initiation period, as they are expected to remain indoors. This restriction can lead to pregnancy complications or even death.”

Ogo cultural traditions and other contextual factors around masculinity heavily shape men’s and boys’ access to healthcare in Nigeria and, because of their roles as decision-makers in the family, affect women’s access to healthcare and well-being. Socio-cultural norms strongly influence women’s access to reproductive and maternal healthcare, which is unattainable without the support from community leaders, predominantly men. According to a 2016 study in Ebonyi and Kogi States, “ninety-eight percent [of healthcare providers] believed men should participate in health services… only 10% encouraged women to bring their partners.” The same study reported the observance of “harmful practices… in 59.6% of deliveries and disrespectful or abusive practices … in 34.0%.”

With consideration of these factors, WI-HER, through a US Agency for International Development (USAID) project, the Integrated Health Program (IHP), collaboratively—with community leaders, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders—developed activities to specifically engage men as patients and advocates for their own health, as well as the health of their female partners and children. WI-HER believed that this would not only increase men’s access to healthcare but also increase women’s and children’s use of healthcare services since research has shown that male engagement in healthcare has increased the use of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCAH) services,

Ogo Culture, Masculinity, and Healthcare Access

More specifically, studies show that men’s involvement in RMNCAH increases birth preparedness and improves maternal health services and mental health, overall improving maternal and newborn health outcomes.

But how does it affect men’s access to healthcare as patients themselves? In Nigeria, men’s access to healthcare is shaped by gendered norms around masculinity, leading to many men hiding illness or pain to avoid the stigma of going to healthcare facilities for fear of appearing weak.

There are also widespread misconceptions around medicine and healthcare; Pastor Chima says that prior to USAID’s efforts through IHP, “We believed that women in labor should give birth behind the house instead of going to the healthcare center, resulting in high maternal death rates. Our community had great faith in traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and regarded cultural practices as superior to modern medicine. People also trusted the potency of herbal medicine and viewed pharmaceutical drugs as poison. Additionally, there were fears about vaccines, with a belief that they could harm children.”

The Ogo cultural restrictions on access to healthcare further compound these issues in Ebonyi State. Elder Onu Kalu Omaka, Ward Development Committee (WDC) Chairman of the Etiti Model Primary Healthcare Center, says, “Ogo culture is really affecting our men as they tend to believe that they are stronger and that anyone in the Ogo [culture] within the incubation period is not allowed to seek healthcare.” Mrs. Ola Oko Arua, Officer-in-charge for Etiti Model Primary Care Facility, further explains, “During Ogo festival (a cultural celebration performed by the men), men are always engrossed in this activity that they ignore even urgent health needs of their wives and children.” Furthermore, community members often perceived healthcare facilities as a gendered space in which it was culturally appropriate for women and children to enter and access services but not for men and older boys.

Responding to the Unique Health Needs and Roles of Men and Women in Healthcare

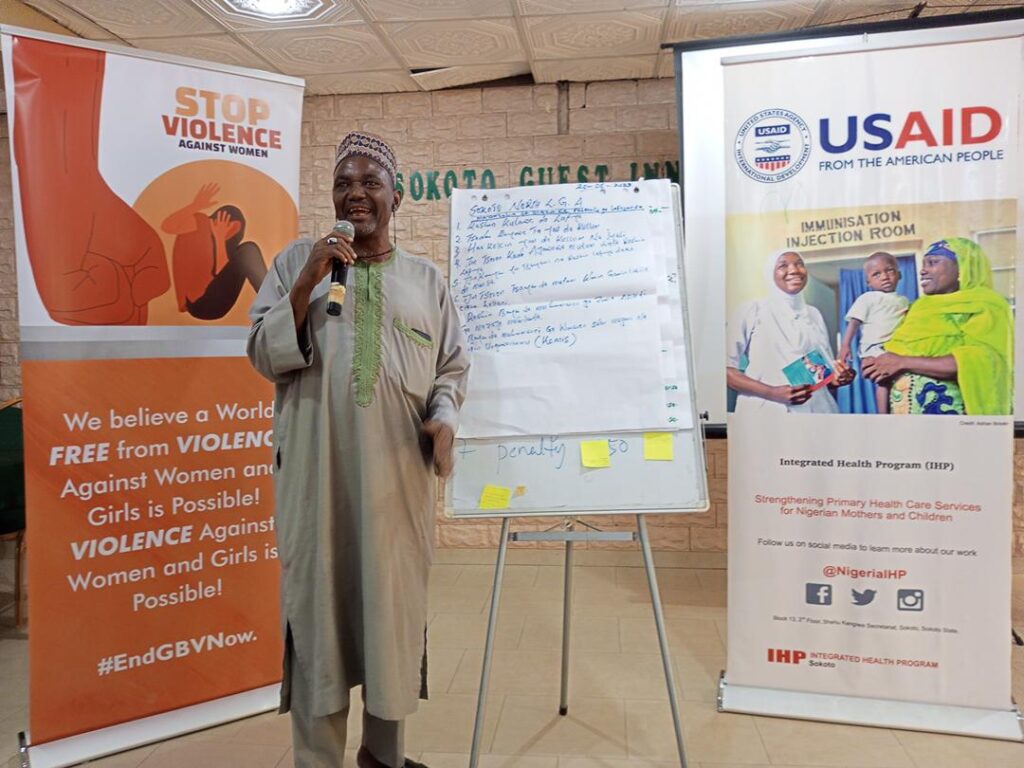

Starting in 2019, to address societal norms and expectations around masculinity limiting men’s and boys’ access to healthcare services, WI-HER worked with community stakeholders, including Ward Development Committees, primary healthcare facilities, and other government organizations, to develop and implement male engagement activities.

WI-HER utilized its iDARE™ methodology, based on the science of improvement, and partnered with state and local government agencies and healthcare facilities to co-develop contextually appropriate solutions and male engagement activities that addressed root causes, such as sociocultural constructions of masculinity in Ogo culture, ultimately leading to fundamental shifts and sustainable outcomes.

To facilitate men’s participation in the health system and their utilization of services, State level actors and providers in facilities recognized that they needed to take proactive steps to engage men in health activities, including soliciting their input in health service design, inquiring about their health concerns and needs, and leveraging their community leaders to educate populations on how to protect themselves and their families. WI-HER GESI Advisor Augustine Onwe explains:

“To ensure the sustainability of the Male Engagement in RMNCAH initiative, we collaborated with members of the Ward Development Committees (WDCs) and healthcare workers at primary health facilities to develop community-driven action plans. These plans focused on the ongoing and consistent mobilization of men at the community level to improve health outcomes by promoting maternal and child health, supporting women’s reproductive choices, and eliminating gender and social barriers that hinder access to healthcare for men, women, children, and young people. Healthcare workers were also coached to provide inclusive and equitable healthcare services at the facilities.”

Through these plans and related workshops, stakeholders agreed on community and facility-level activities, including the provision of a convenient and separate waiting area for men in facilities and the use of social gatherings like naming ceremonies, weddings, and places of worship to hold community dialogue on early antenatal care (ANC), healthcare for sick children, and childhood immunization.

Mr. Onwe emphasizes, “PHCs are owned by the communities, and the WDC represents the community interest in the management of the health facilities. The workshop on male engagement gave the WDC leadership an opportunity to understand the role of men in advancing access to healthcare services for themselves and their families and to learn how they can leverage existing structures and events at the community level to mobilize men as clients, supportive partners, and agents of change and improve demand and utilization of health care services at the Primary Health facilities in their communities.”

Male Engagement Activities

To tackle harmful socio-cultural norms around masculinity at the healthcare facility level, stakeholders agreed on activities that included training healthcare providers on how to engage with men as clients and the importance of male allyship in their families’ access to healthcare, as well as identifying and engaging male champions at the community level to provide information on accessing healthcare services and the importance of their family’s access to healthcare (particularly around RMNCAH and immunization).

By training healthcare professionals on engaging men in routine services and during antenatal and postnatal visits, WI-HER and its partners created an accessible environment where men feel comfortable accompanying their families to appointments. Through this process, healthcare workers noticed that men didn’t have access to appropriate waiting areas while their partners and children received care, so WI-HER worked with healthcare facilities to create safe and more appealing spaces for men (e.g., waiting rooms, male-friendly spaces, and private delivery areas so men can attend with their partners).

Mrs. Egbechi Oji Imo notes that these trainings taught her about “Greeting… them with the respect due to them. Creating a friendly atmosphere each time I am interacting with them. Also, respecting their cultural values… [and] providing gender and health education to the men.” The male engagement trainings for healthcare providers in facilities helped them learn how to talk with men to elucidate their health needs and those of their families, and be willing to respond to men’s needs in healthcare facilities.

Trained healthcare professionals then trickled down information to communities; as Mrs. Egbechi Oji Imo, Officer-in-charge for Nguzu Primary Care Facility, explains, “I used the Ward Development Committees to pass information to men in the community. I equally give them health education each time they come to the health center and sensitizing them during community meetings.”

WI-HER’s engagement within healthcare facilities was complemented by other USAID implementing partners’ work in communities. Partner organizations engaged in advocacy within communities, focusing on traditional and religious leaders, to provide information on the importance of accessing healthcare and how to do so. Furthermore, there are almost always men in these communities who support health-seeking behaviors and are involved with their families’ health; implementing partners identified and engaged these men as ‘male champions’ to promote community buy-in and sustainability.

Pastor Chima, one such ‘male champion,’ says that, through USAID IHP, “We learned about the importance of positive health-seeking behavior and the need to encourage and support women and children in accessing care at health facilities. We also learned about the various healthcare services available at these facilities.”

Now, Pastor Chima shares this information in his sermons: “I… used my church platform to share information about the importance of healthcare and good health-seeking behavior with the wider community.” Elder Onu Kalu Omaka is also heavily involved after meeting with IHP: “I have taken it upon myself to go round the village to seek for pregnant women who are yet to register for ANC, as well as… educate our men in the community [on health].”

Lastly, WI-HER worked with healthcare facilities to ensure that data on male participation in health services, including male accompaniment of female partners and children,was collected and included in the national-level health data dashboard. Monitoring and evaluating male engagement programs is vital to determining the relative success of different strategies, providing data for program improvement, and presenting evidence of the impact of involving men. Measuring change in male utilization of services (as clients and as partners) helps gauge male engagement in health systems and, from a structural perspective, allows the government to promote and monitor the inclusion of male health-friendly services (e.g., vasectomy in family planning) in guidelines, strategies, regulations, or policies.

Results of Male Engagement Activities

These activities at the facility and community level resulted in more men seeking health services for themselves and supporting their partners and children in accessing healthcare. Mrs. Ola Oko Arua recounts a story about a man “who was present during one of my community sensitizations on male engagement stopped his wife from going to the [traditional birth attendant] for delivery. He personally brought his wife to my health facility, and the woman had a successful delivery.”

Pastor Chima also shares: “Before now, men in this our community often believe that health centre is only for women and children, but after which I educated them on the need to always go to health center to check their BP, treat malaria, and other things and let them know that our [officers-in-charge] are efficient, men’s perspective toward health changed for good.”

Similarly, Mrs. Egbechi Oji Imo says, “More men now come with their wives during ANC, immunization, and support during labour delivery, etc., and come out during health outreaches conducted within the community.”

Additionally, men are now more informed and engaged in the health of their spouses, leading to improved communication and support between couples. This has also encouraged men to take better care of their own health, promoting proactive behavior in seeking medical attention when necessary. For women, the benefits of male involvement in healthcare are significant. With the support of their spouses, women are more likely to attend antenatal care appointments, which improves ANC retention, increases delivery in health facilities, leads to more healthy babies, and increases the likelihood of women seeking postpartum care. This results in overall improved maternal and child health outcomes, leading to healthier families and communities. The men also act as agents of change, championing the cause in the community, and village heads and community leaders are now educating their wards on the importance of healthcare.

Our Work Isn’t Done

The future is not certain, though. Culturally-appropriate advocacy needs to continue within communities and with healthcare providers, alongside free services or increased access to health insurance, since the healthcare costs are a limiting factor. Also, although healthcare facilities have begun to track data (on the number of men accompanying their partners or children to services, or accessing services themselves), it will require more time to see the real, long-lasting impact of these male engagement activities. The narrative findings thus far are promising, and this work will continue as male champions and trained healthcare professionals continue to work toward greater access to healthcare for men, women, and children in their communities.