Mental Health is a Human Right: Greater Awareness and Capacity Building Support is Needed in Ethiopia and Beyond

By Krista Odom, WI-HER Program Coordinator

Prior to the pandemic, a significant treatment gap existed in mental health services and resources when comparing high-income countries (HICs) to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Today, a year-plus into the pandemic, that gap continues to widen.

Making the work of the global development community particularly difficult is the lack of time-trend regression models that forecast mental health concerns, such as an increase in suicide risk, particularly in LMICs. Country governments, donors, researchers, development practitioners, and communities – we all have an important role in support of global mental health, and how we help those most at risk and vulnerable.

One of the first people to befriend me when I moved to Ethiopia as a Peace Corps Volunteer was Dinkinesh, or Dink. We came to know each other in a remote village of less than 1,000 people in the Amhara District, two kilometers up a mountain from the nearest road, 15 kilometers from the nearest city, Dessie, and 415 kilometers from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, and the nearest and only mental health specialty hospital in the country.

Dink was approximately 11 years old and suffered from an undiagnosed developmental disability, likely a severe autism spectrum disorder. I first met her when I ventured into my new community for the first time on a particularly hot day to find something cold to drink. I used my basic language skills to ask where I could find a cold drink and was brought to the only shop with a refrigerator in town. I bought a cold orange flavored mirinda and sat down in the shade nearby to enjoy my drink. It did not take long before Dink wandered over and pointed at my mirinda and made grasping motions. She sat down next to me and waited impatiently, continuing to communicate her wants. I sipped a bit more of my cold mirinda and handed the remaining drink to Dink. This became our tradition.

Background

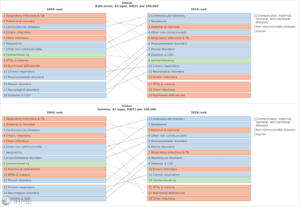

The prevalence of mental health disorders has been rising globally due to demographic, environmental, and sociopolitical transitions, according to The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development. In the last 30 years mental health disorders have risen from the 13th leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) to the 7th leading cause, as can be seen in the accompanying graphic. Additionally, risk factors associated with common mental disorders—including discrimination, history of abuse, and higher rates of interpersonal stressors—equates to differences between the sexes on prevalence. The rates for DALYs for mental health disorders for males globally is 1,464.84 per 100,000 and is the 11th highest cause of DALYs in 2019. For women it is 1,755.22, and is the 6th highest cause of DALYs.

Projections indicate increased burden of mental health disease will continue, and the greatest impact will be in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). While there is an increase in mental illness prevalence, many LMICs are simultaneously experiencing a gap in human resources for health care, particularly for mental health. There is an estimated 1.2-million-person gap needed to provide mental health services, and nearly 90% of mental health patients have not seen medical professionals in LMICs.

In Ethiopia, there are 60 psychiatrists and one mental health specialty hospital, even though Ethiopia has a population of approximately 100 million. That means that for every psychiatrist, there are 1,666,6667 Ethiopians. The prevalence of mental health disorders in Ethiopia is conservatively estimated at 18% for adults and 15% for children. This translates to at least 16.5 million people suffering from mental illness in a country with 60 psychiatrists. If all of those suffering in Ethiopia sought care, the patient load for one psychiatrist would be 275,000 patients. For Dink, there are two specialists in Autism Spectrum Disorder, both of which live and practice in Addis Ababa.

While there have been advances in the development of evidence-based practices for treating and preventing common mental health disorders, the uptake has been especially slow in LMICs. This slow uptake is, perhaps, due to the vast shortage in human resources, the continued growth in the burden of disease, and stigma toward and discrimination against those suffering from mental illness and their families. These barriers to care often lead to cases of human rights violations that disproportionately impact women as victims.

In Ethiopia, persons living with mental illness may be imprisoned in their homes, sent to religious encampments where deprivation of food is common, or sent to the streets to survive as they can. For women, these outcomes are particularly dangerous. Dink was lucky in regard to these norms; she was not in school or out playing with other children, but her parents had not imprisoned her in the home. While not spoken of, during holidays children and family members that I had never seen in public were suddenly in the fields at dawn on Eid Mubarak, praying East to Mecca, or in the Orthodox Church for Easter to atone and receive forgiveness. Those family members were stashed away to prevent the public from seeing their conditions, due to discrimination against people living with mental illness and their family members.

Dink became a companion. When I left for hikes around the lake or up the mountain she came along, and we shared our cold mirinda when we made it back home. On market days, she sat with me at breakfast and ate bread she dipped in her sugar laden tea. This went on for the first eight months of my 2 year stay.

Then I stopped seeing Dink.

She was no longer my breakfast companion. She didn’t appear when I stopped by the shop for a cold mirinda. She wasn’t even there at Timket the orthodox celebration, when all other Christians attended the ceremony. I asked around trying to find her, but the topic was avoided. One day, while visiting friends in the nearest city, I spotted Dink. She was barely clothed, dirty and living on the street.

After some digging I found out the family had been ostracized for Dink’s illness. Her mother was no longer getting jobs cleaning peoples’ homes, and no one was coming to their family compound to buy Tela, a traditional drink, that the family sold. Their livelihood was disappearing as Dink became more of a fixture in the village. The family decided the only option was to leave Dink on the streets to survive for herself.

Conclusion

While I never again saw Dink after that day in Dessie, I know there is no happy ending to her story. And she is not unique in Ethiopia or any other country in the world. Resources for mental health are scarce, and stigma is high in many western countries, including the United States. The ongoing COVID-19 crisis, compounded with resource reallocation to fight the virus, and increase in environmental stressors on the entire global population are immeasurable in their impact on mental health.

When I left Peace Corps, I enrolled in a research program that partnered with Addis Ababa University to close the gap of human resources for mental health care by delegating to primary healthcare providers in an effort to task shift. Task shifting refers to the strategy of redistribution of mental health care within the existing health workforce, such as by training providers to diagnosis and treat common mental health disorders. In Ethiopia, there is one psychiatrist for every 1.67 million Ethiopians; the only current solution is to integrate care into the larger healthcare system to alleviate the untenable burden on highly trained mental health providers. Instead, common mental health disorders are treated locally in health centers by primary health care providers, while severe cases may be referred to the few psychiatrists available. Cases like Dink, who may have had the ability to learn some life skills through occupational therapy, still did not have access to the appropriate treatment.

In the integration of mental health into primary care, healthcare providers were trained in screening, diagnosing, and treating common mental health disorders. Medication for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and seizure disorders were added to the essential medications policies. Social behavior change campaigns were designed to address issues of stigma and discrimination by the community and the healthcare workers. And policies were being put in place in the 2020 scale up for psychiatrist incentives for hardship posts outside of the capital in order to increase coverage for severe case patients and oversight for providers.

While this integration of mental health care into primary health care is a step in the right direction, it is far from enough, especially when considering that it does not address how many individuals with mental illnesses are subjected to human rights violations both inside and outside hospitals and health facilities. We, as part of the global development community, must do, and offer, more if we are to meet the needs of those suffering from mental health disorders and help those most impacted.