Learning from Zika – and Beyond

By Morgan Mickle, Gender Specialist, WI-HER, LLC

We have a lot to learn from Zika. And we better pay attention.

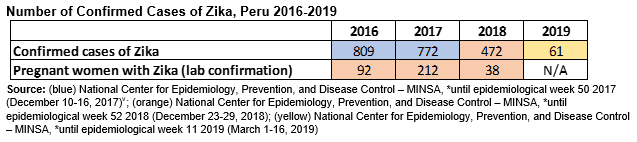

Many believe that Zika is no longer a threat, but think again. In the first three months of 2019 alone, there were 61 confirmed Zika cases reported in the country.[i] In Peru’s far northwest region, there have been 19 confirmed cases in Piura between January and the first week in May, [ii] and 15 suspected cases of Zika among pregnant women in Tumbes between January and mid-June.[iii] Last year in 2018, there were 472 confirmed cases of Zika, 38 of which were pregnant women.[iv] While the data show a downward trend from the last year, the reported cases this year from just two departments are startling, and must be recognized and watched. Zika has been recorded across the Latin American and Caribbean region for potential impacts to babies and children born to mothers who had the virus during pregnancy including, microcephaly and other congenital malformations.

The USAID ASSIST Project is using data to collaborate, learn and adapt. Specifically, ASSIST Peru is using the data from Piura and Tumbes to re-initiate Zika-related data collection and reporting in those departments. The lessons we learned from the first reports of ZIKA at the outset of the 2015 outbreak taught us that we must respond quickly even to early signals. WI-HER conducted a landscaping analysis in Piura and Tumbes in May 2019 and learned that neither providers nor clients were aware of the rising numbers of ZIKA confirmed and suspected cases in their area. Without that information, pregnant women and their partners did not feel any urgency to use condoms during their pregnancy to protect their unborn children from possible effects of the Zika virus. Further, without the data, providers did not sense a need to screen all pregnant women for Zika. That is changing. WI-HER, from the data gathered during the landscaping analysis, collaborated with the ASSIST Peru team, who now have passed that learning on to the Piura and Tumbes Regional Directorates of Health to adapt the Ministry of Health messaging to providers and clients and to initiate more pro-active screening.

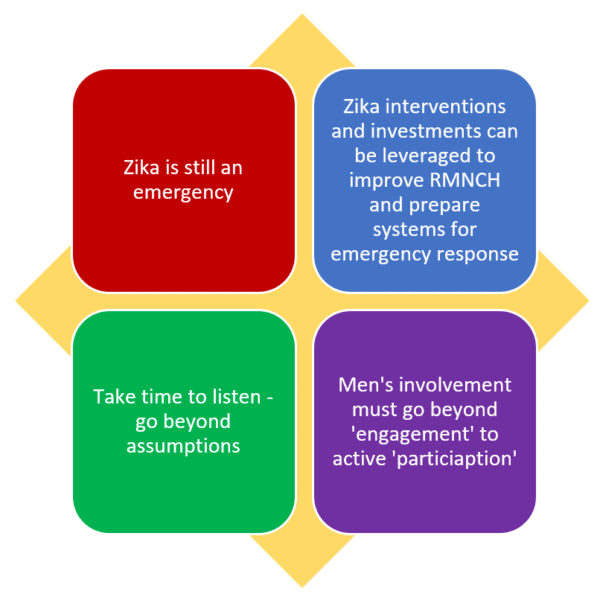

During our work with USAID’s Zika response, WI-HER has learned other lessons as well: 1) Zika is still an emergency, 2) Zika interventions and investments can be leveraged to improve RMNCH and prepare systems for emergency response, 3) We must take time to listen – go beyond assumptions, and 4) Men’s involvement must go beyond ‘engagement’ to active ‘participation’.

Last month USAID and Knowledge for Health hosted a workshop, “Learning from Zika: Lessons for future public health emergencies, through which experiences and learnings were shared and discussed. WI-HER was among the invited implementing organizations who have partnered with USAID’s Zika response in Latin American and the Caribbean. We were invited to share some of our key lessons learned during our support to emergency preparedness and response and to improving health systems to better provide for maternal, newborn, and child health.

A leader in gender integration in health systems strengthening under the ASSIST Project, I was pleased to represent WI-HER in leading a “Buzz Station” (or small table conversation) to share and discuss some of our key learnings from this past year. The collaborative sharing sparked further discussions on how current programs might be adapted to incorporate lessons learned and through our current and future support to country partners. WI-HER shared four key discoveries that shaped our messaging and training design with our partners in Latin American and the Caribbean:

A leader in gender integration in health systems strengthening under the ASSIST Project, I was pleased to represent WI-HER in leading a “Buzz Station” (or small table conversation) to share and discuss some of our key learnings from this past year. The collaborative sharing sparked further discussions on how current programs might be adapted to incorporate lessons learned and through our current and future support to country partners. WI-HER shared four key discoveries that shaped our messaging and training design with our partners in Latin American and the Caribbean:

Zika is still an emergency

We must continue to monitor the Zika situations in the countries where we work. The publicly available information through PAHO/WHO web platforms (where development agencies and practitioners would likely find data) are outdated, leaving one to wonder about the real-time situation.[a] The implications for not having this information at the donor level could be that Zika becomes a less relevant issue, taking funds away from a real need and to seemingly other more pressing needs. At the community level, the absence of international monitoring or reporting on Zika can signal to providers that Zika as not applicable in their communities, further leading to complacency when vigilance is needed. In fact, in Peru we learned from pregnant women themselves that not everyone is being tested for Zika, and a number of women expressed their desire for additional up-to-date information and testing. In addition, if care seekers in communities are not aware of active Zika and they are not being told about it from health providers or other sources, then they are left vulnerable and unable to make informed decisions that can protect their family – such as using a condom during pregnancy to prevent sexual transmission of the Zika virus. Here’s the kicker…the locations where we were in Peru – where none of the women or men we interviewed use condoms during pregnancy to protect their children (Piura and Tumbes) – actually are among the highest areas for Zika in the country. We must continue to message about Zika so that health providers, care seekers, and all community members know that Zika remains a real threat.

Zika interventions and investments can be leveraged to improve RMNCH and prepare systems for emergency response

We must integrate our technical assistance and learning around Zika into related health interventions for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health; psychosocial support; and male engagement to maximize our dollars. This has been done under ASSIST to some extent and is evident in interventions such as those done under the project in the Eastern and Southern Caribbean where Zika emergency response has been used to strengthen well-baby and well-child care, but all Zika implementing partners can push ourselves more in this regard. One way is to focus on integrating outbreak response efforts. As Irene Koek, Senior Deputy Assistant Administrator for USAID’s Global Health Bureau stated during the workshop’s opening remarks, “working to improve existing systems rather than creating parallel ones is paramount”. We can look to dengue as an example. The virus is on the rise and many of the same vector control and messaging around Zika are applicable. According to most recent February 2019 PAHO/WHO’s Epidemiological Update for Dengue[vi], there were 560,568 cases of dengue reported in the Americas in 2018; 336 of which resulted in death. Dengue and Zika are closely related and are passed by the same mosquito. Additionally, in 2018 a study in the Eurosurveillance journal found dengue virus in the sperm of a man 37 days after infection.[vii] A 2019 article – while citing dengue found in plasma, urine, saliva, and vaginal secretions – however determined that sexual transmission of dengue is rare and not of current public health significance.[viii] While the detection in semen and elsewhere is not direct proof that the virus can be passed sexually, it does show that it is a possibility and that the virus can pass through other bodily fluids, and information researchers should keep their eye on in light of the Zika epidemic. Looking towards future public health emergencies we must leverage investments and adapt our interventions according to lessons learned so that we continually strengthen health systems to respond promptly and effectively.

Take time to listen – go beyond assumptions

We must listen to the communities where we work and tailor responses to meet their needs and close health gaps. It is important that we do not assume. One example related to Zika is that we sometimes assume the men are the ones who stand in the way of women’s wish to use condoms, thus increasing women’s vulnerability and exposing them to higher risks of contracting Zika virus or other sexually transmitted diseases. In Peru, we found differently. Women in Tumbes and Piura didn’t report that they did not use condoms because of their partners. They revealed that they themselves didn’t want to use condoms. In fact, in one group of women we spoke to, 8 out of 8 women reported not using condoms, and 6 out of those 8 reported never using condoms.

“It’s not just the men, sometimes there are women who make the decision not to use the condom.” – Health Provider, Chulucanas Hospital Manuel Javier Nomberto, Piura, Peru May 2019

“Condoms, I don’t use them. It doesn’t feel the same.” – Female Care Seeker, Peru-Korea Friendship Hospital Santa Rosa, Piura, Peru May 2019

Separate findings from discussions with women in Antigua revealed that women there are very empowered to use condoms and do so or don’t engage in sex at all. However, one woman noted and others agreed that once people are using some other form of contraception they tend not to use condoms.

“No condom? Lock down shop.” – Female Care Seeker, Antigua, May 2019

“No condom no sex.” – Female Care Seeker, Antigua, May 2019

“Once they have contraception, they don’t remember what a condom is.” – Female Care Seeker, Antigua, May 2019

Taking the time to dispel our own biases and listen to our surrounding communities can help ensure our interventions are more effective. We must now think about our condom messaging for both men and women and find new ways to encourage condom use.

Men’s involvement must go beyond ‘engagement’ to active ‘participation’

We must involve men in their own heath in addition to that of their partner and families. There are instances where men are involved in their partner and child’s health, but generally we found that both clients and health providers identified male participation at health facilities as low. On average in Peru health care providers identified male involvement only 10-20% of the time. In Antigua this trend is changing, and men are starting to come increasingly with female partners and children for prenatal and well-child visits; yet still not as frequently for their own health. We found through our capacity building activities with health providers in Peru that when men were active in their own health and that of their family’s they reported feeling more confident, invested, and part of health decisions. We can learn from this experience and better reach out to men directly.

The next public health emergency is coming, but spaces such as this Learning from Zika workshop provide us with opportunities to collaborate, share learning, and go forward with the knowledge and tools to lead timely and effective responses. To quote the movie Toy Story, we now have the opportunity to take what we learned and go “to infinity and beyond”. We’re up for the challenge.

From 2012-2017, the USAID ASSIST (Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems) Project fostered improvements in 38 countries in a range of health care processes through the application of modern improvement methods by host-country providers and managers and build the capacity of host-country systems to improve effectiveness, efficiency, client-centeredness, safety, accessibility, and equity of the health services they provide. In a two-year extension from 2017-2019, ASSIST applies quality improvement methods to health systems strengthening efforts in Zika-affected countries, including Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, St. Kitts and Nevis, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

WI-HER, LLC (Women Influencing Health, Education and Rule of Law) is a woman-owned small business that partners with international donors, national governments, non-governmental organizations and others to identify and implement creative solutions to complex development challenges to achieve better, healthier lives for women, men, girls, and boys. Founded by Dr. Taroub Harb Faramand in 2011, WI-HER, LLC works to integrate gender through contextualized, adaptable, and systems strengthening methods that can be seamlessly integrated into ongoing and new programs. WI-HER is committed to ensuring equal opportunities for women, men, girls, and boys, as well as all other vulnerable groups, including LGBTQI+ people.

[a] The PAHO/WHO Cumulative Zika Case table was last updated January 4, 2019 and the PAHO/WHO Epidemiological Reports were last updated September 25, 2017

[i] http://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/boletines/2019/11.pdf

[ii] https://diresapiura.gob.pe/documentos/Boletines%20Epidemiologicos/BOLET%C3%8DN_18.pdf

[iii] http://www.diresatumbes.gob.pe/index.php/boletines-epidemiologicos/boletines-epidemiologicos/category/111-boletines-2019

[iv] https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/boletines/2018/52.pdf

[v] https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/boletines/2017/50.pdf

[vi] https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=dengue-2217&alias=47782-22-february-2019-dengue-epidemiological-update&Itemid=270&lang=en

[vii] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6053624/

[viii] https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/26/3/tay157/5259064